Just finished up a two-day workshop with Dan Beck, a modern master of the American Impressionist society. Here I will share some of the tips I learned while in St. Simons, Georgia.

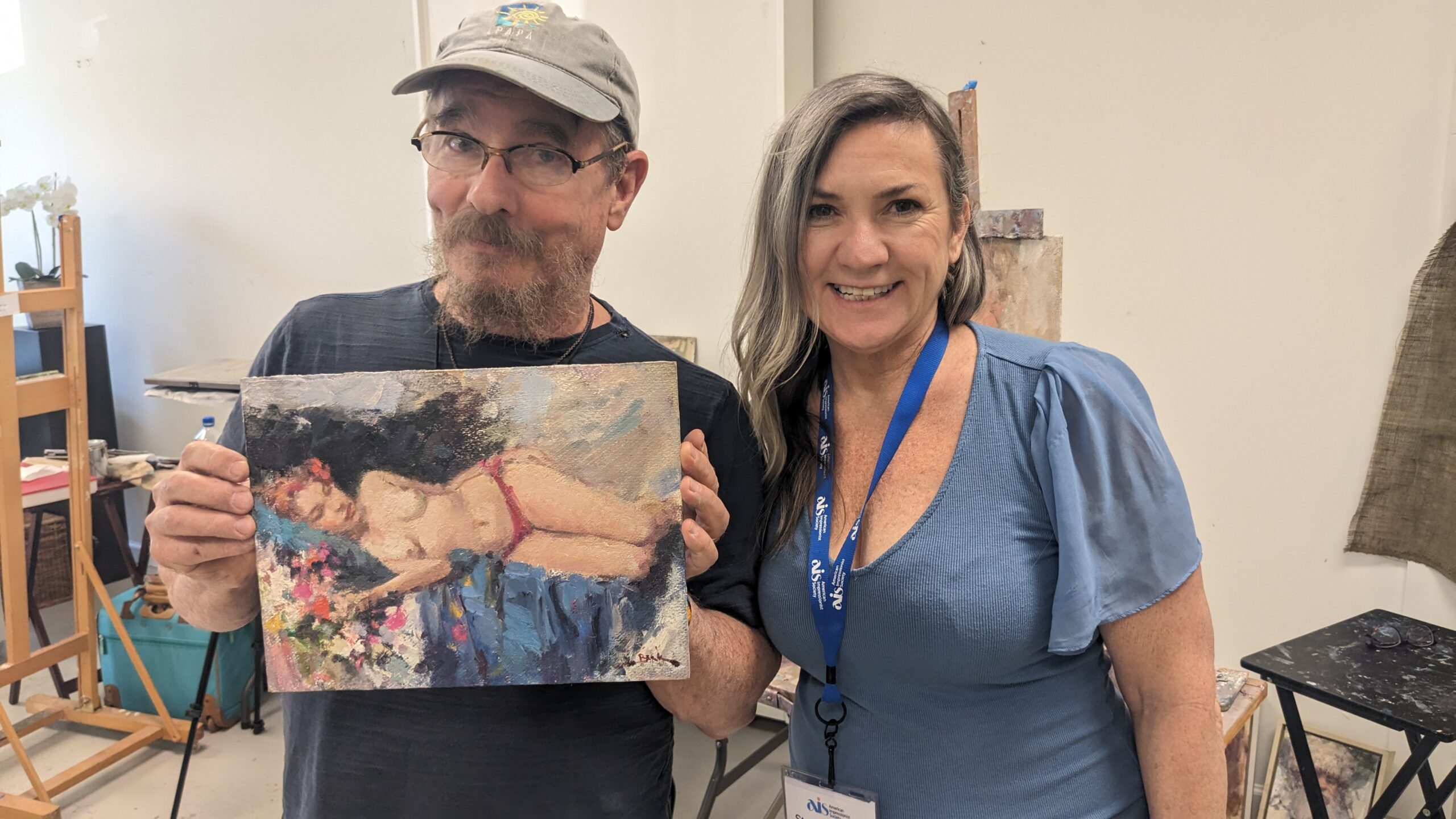

It was the first time I ever worked with a live model (two at that) and my first event with AIS. It really was a terrific experience. I took copious notes, painted two portraits in profile, and purchased a 9×12 piece of art that I love from Dan.

The most important lesson I learned is to be a rebel. As artists, we’re taught the “rules.” There is no finer “rule-breaker” than Dan. Though he did stress the importance and difficulty of mastering the seven elements of art: The seven elements of painting are line, shape, edges, value, form, texture, and color.

Some of the rules we are taught that Dan doesn’t follow are:

- Never use black. Dan uses black.

- Only use expensive materials. He uses any substrate including masonite and Winsor Newton too.

- Make every stroke count. Dan paints wrong then finds right. He even uses an orbital sander to remove sections, paints on top of it, constantly pushes and pulls, adds and subtracts, until the painting emerges.

- Always paint from life. Dan loves to paint from life but takes photos so he can paint from them after the studio session. This provides an added sense of freedom.

- Shadows must be transparent and thin. Not true. The Russian Impressionists used only opaque paints and painted thick shadows.

- Shadows must be cool. Also, not true. Shadows vary based on lighting and subject.

- It is true that realists measure everything. Dan does not. He is not a portrait artist, he is an impressionist. That means, he connects with his subject and paints their essence, even if it doesn’t look just like the person. The Russians exaggerated features and made more of a caricature painting in their own styles. If you want to be a realist, measure. If you want your own expressive personality in the paintings. don’t.

- Only use an oil primed substrate. Dan likes the absorptive properties of acrylic gesso.

- Don’t add white until the end. Dan establishes his light and dark values from the start so that the relationships may be established during the painting process.

- Dan doesn’t subscribe to using the largest brushes at the beginning and saving the smaller brushes until the final details. He uses whatever brush he intuitively needs whenever he wants.

- If you’re not creating a masterpiece, why bother. Another false statement in Dan’s opinion. Practice skills and subjects where you feel you would like to grow. Draw quick sketches and thumbnails to help you keep in good form.

Some of the other interesting notes are that Dan doesn’t use umbers, he mixes his own. He uses a limited palette of typically a warm and a cool red, blue and yellow with white and black. Sometimes he uses a green or black as the blue. His favorite colors this week are Winsor Newton permanent rose, cad yellow light and ivory black. Viridian is on his palette as a convenience color. His browns tend to lean towards purple.

He begins on a toned canvas by blocking in his sketch with line and a middle tone wash of semi-monochromatic color masses for his underpainting, grouping masses into shapes to get the design started. Beck works the entire canvas as he goes. Not only can color masses move the eye around the canvas but also grouping saturation levels can also achieve the same effect… so keep grays together and areas of higher chroma. Nature has light. Painters have color, value and vibration. Use it all.

He values high contrast (you can call them opposites) of everything… line, shape, value, color, abstract vs realism… everywhere you can bring contrast is more interesting than when everything is similar. He establishes a rhythm of push and pull with intuitive colors. He uses multiple brushes but isn’t good at keeping them separated, though he does wipe paint off his brush after he loads it. Dan quoted (I believe) fellow AIS Master Carolyn Anderson by saying “The artist with the most contrast wins.”

While he may have established an alla prima (wet on wet) routine at some point during his career, he now paints in layers. Letting them dry, sanding them down, building up texture, abstraction, even mark making to keep loose, calligraphy and asemic writing, adding and subtracting by whatever means. On the painting I purchased, you can literally see marks of the orbital sander.

Sometimes, he’ll use Liquin. Other times not. He literally has an anything goes approach and follows very few steadfast rules… this is extremely freeing for his spirit.

Keep the foreground sharper and more in focus and add atmospheric perspective by softening edges in the background.

Another important lesson I learned from Dan is to figure out, as part of your design, what percentages of realism vs. abstraction, light and dark and other contrasts. They should never be 50-50% but rather closer to a dominance of one of the opposites. For an impressionistic style, abstraction dominates over realism. Keep detail in the face but make the background areas that aren’t the focal point more impressionistic.

The most important thing is to get the lighting right. Simplify light and form. Don’t resist drawing from your classical training in shapes and wedges while drawing in circles for rhythm and straight lines for accuracy. Keep the lights light and the shadows shadows and leave your brush strokes between tones. This is more complex than you think.

Photo gallery of the 2-day workshop with Dan Beck.